(don't worry about the 'index' and 'value' stuff; it's not important just now)

(don't worry about the 'index' and 'value' stuff; it's not important just now)And What About Functions and Sound?

I've probably bored you enough with technical details, so let's get back to making noise, which I assume is why you're reading this after all. Trust me though, all this work will pay off later, and believe it or not, we've already covered a fair amount of the basics of the language, at least in passing.

Let's go back to our sound example, or rather a slightly simplified version of it. Check that the localhost server is running, execute the code below and then press Cmd-. when you've had enough.

{ SinOsc.ar(440, 0, 0.2) }.play;

In this case we've created a Function by enclosing some code in curly brackets, and then called the method 'play' on that Function. To Functions 'play' means evaluate yourself and play the result on a server. If you don't specify a server, you'll get the default one, which you'll recall is stored in the variable 's' and is set at startup to be the localhost server.

We didn't store the Function in a variable, so it can't be reused. (Well, actually you could just execute the same line of code again, but you know what I mean...) This is often the case when using Function-play, as it is useful as a quick way of getting something to make noise, and is often used for testing purposes. There are other ways of reusing Functions for sounds, which are often better and more efficient as we will see.

Lets look at what's between the curly brackets. We're taking something called a 'SinOsc' and we're sending it the message ar, with a few arguments. It turns out that SinOsc is an example of something called a class. To understand what a class is, we need to know a little more about OOP and objects.

In a nutshell, an object is some data, i.e. some information, and a set of operations that you can perform on that data. You might have many different objects of the same type. These are called instances. The type itself is the object's class. For instance we might have a class called Student, and several instances of it, Bob, Dave and Sue. All three will have the same types of data, for instance they might have a bit of data named gpa. The value of each bit of data could be different however. They would also have the same methods to operate on the data. For instance they could have a method called calculateGPA, or something similar.

An object's class defines its set of data (or instance variables as they are called) and methods. In addition it may define some other methods which only you send only to the class itself, and some data to be used by all of its instances. These are called class methods and class variables.

All classes begin with upper-case letters, so it's pretty easy to identify them in code.

Classes are what you use to make objects. They're like a template. You do this through class methods such as 'new', or, in the case of our SinOsc class above, 'ar'. Such methods return an object, an instance, and the arguments affect what its data will be, and how it will behave. Now take another look at the example in question:

SinOsc.ar(440, 0, 0.2)

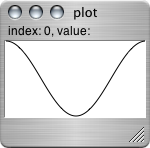

This tells the class SinOsc to make an instance of itself. All SinOscs are an example of what are called unit generators, or UGens. These are objects which produce audio or control signals. SinOsc is a sine wave oscillator. This means that it will produce a signal consisting of a single frequency. A graph of it's waveform would look like this:

(don't worry about the 'index' and 'value' stuff; it's not important just now)

(don't worry about the 'index' and 'value' stuff; it's not important just now)

This waveform loops, creating the output signal. 'ar' means make the instance audio rate. SuperCollider calculates audio in groups of samples, called blocks. Audio rate means that the UGen will calculate a value for each sample in the block. There's another method, 'kr', which means control rate. This means calculate a single value for each block of samples. This can save a lot of computing power, and is fine for (you guessed it) signals which control other UGens, but it's not fine enough detail for synthesizing audio signals.

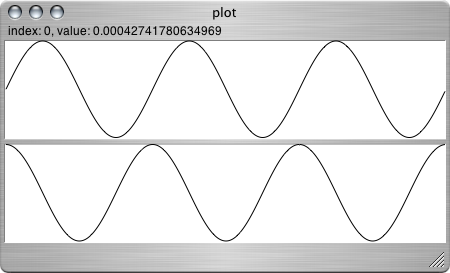

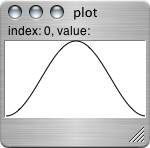

The three arguments to SinOsc-ar given in the example determine a few things about the resulting instance. I happen to know that the arguments are frequency, phase, and mul. (We'll get to how I know that in a second.) Frequency is just the frequency of the oscillator in Hertz (Hz), or cycles per second (cps). Phase refers to where it will start in the cycle of its waveform. For SinOsc (but not for all UGens) phase is given in radians. If you don't know what radians are, don't worry, just understand that it's a value between 0 and 2 * pi. (You can look at a trigonometry text if you really want more detail.) So if we made a SinOsc with a phase of (pi * 0.5), or one quarter of the way through its cycle, the waveform would look like this:

Make sense? Here are several cycles of the two side by side to make the idea clearer:

So what about 'mul'? Mul is a special argument that almost all UGens have. It's so ubiquitous that it's usually not even explained in the documentation. It just means a value or signal by which the output of the UGen will be multiplied. It turns out that in the case of audio signals, this affects the amplitude of the signal, or how loud it is. The default mul of most UGens is 1, which means that the signal will oscillate between 1 and -1. This is a good default as anything bigger would cause clipping and distortion. A mul of 0 would be effectively silent, as if the volume knob was turned all the way down.

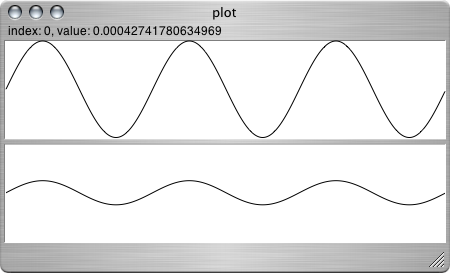

To make clearer how mul works, here is a graph of two SinOscs, one with the default mul of 1, and one with a mul of 0.25:

Get the idea? There's also another similar arg called 'add' (also generally unexplained in the doc), which (you guessed it) is something which is added to the output signal. This can be quite useful for things like control signals. 'add' has a default value of 0, which is why we don't need to specify something for it.

Okay, with all this in mind, let's review our example, with comments:

(

{ // Open the Function

SinOsc.ar( // Make an audio rate SinOsc

440, // frequency of 440 Hz, or the tuning A

0, // initial phase of 0, or the beginning of the cycle

0.2) // mul of 0.2

}.play; // close the Function and call 'play' on it

)

Some More Fun with Functions and UGens

Here's another example of polymorphism, and how powerful it is. When creating Functions of UGens, for many arguments you don't have to use fixed values, you can in fact use other UGens! Below is an example which demonstrates this:

(

{ var ampOsc;

ampOsc = SinOsc.kr(0.5, 1.5pi, 0.5, 0.5);

SinOsc.ar(440, 0, ampOsc);

}.play;

)

Try this. (Again, use Cmd-. to stop the sound.)

What we've done here is plugged the first SinOsc (a control rate one!) into the mul arg of the second one. So its output is being multiplied by the output of the second one. Now lets look at the first SinOsc's arguments.

Frequency is set to 0.5 cps, which if you think about it a bit means that it will complete one cycle every 2 seconds. (1 / 0.5 = 2)

Mul and add are both set to 0.5. Think for a second about what that will do. If by default SinOsc goes between 1 and -1, then a mul of 0.5 will scale that down to between 0.5 and -0.5. Adding 0.5 to that brings it to between 0 and 1, a rather good range for mul!

The phase of 1.5pi (this just means 1.5 * pi) means 3/4 of the way through its cycle, which if you look at the first graph above you'll see is the lowest point, or in this case, 0. So the ampOsc SinOsc's waveform will look like this:

And what we have in the end is a SinOsc that fades gently in and out. Shifting the phase just means that we start quiet and fade in. We're effectively using ampOsc as what is called an amplitude envelope. There are other ways of doing the same thing, some of them simpler, but this demonstrates the principal.

Patching together UGens in this way is the basic way that you make sound in SC. For an overview of the various types of UGens available in SC, see UGens or Tour_of_UGens.

For more information see:

Functions Function UGens Tour_of_UGens

Suggested Exercise:

Experiment with altering the Functions in the text above. For instance try changing the frequencies of the SinOsc, or making multi-channel versions of things.

____________________

This document is part of the tutorial Getting Started With SuperCollider.

Click here to go on to the next section: Presented in Living Stereo

Click here to return to the table of Contents: Getting Started With SC